Chapter Eleven

The 1830s: when European liberals poked up their heads to see if the coast was clear

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars had killed over 3 million soldiers and one million civilians. As a proportion of the overall population, the wars had been every bit as devastating to Europe as the First World War a hundred years later would be. The generation that came out of those wars never wanted to go through that again. The diplomats who wrote the peace treaties made damn sure that democracy would never ever rear its ugly head again in Europe. All across Europe, censors kept the presses under control. Parliaments were limited to sensible men of means. Meetings were prohibited without police approval. Militias were limited to men of property who would support the status quo in times of crisis. Government jobs went to friends of the king.

For the next hundred years, any newly independent European country such as Greece or Belgium was required to pick a monarch from one of the established royal families to rule over them and keep them out of mischief. In fact, “Republic” was such a bad word in Europe that many traditional republics were either turned into kingdoms (such as the Netherlands) or swallowed by nearby empires (such as Venice, by Austria) in order to keep them under control.

Few liberals expected to ever get as far as establishing republics, but just about any change would be an improvement. In France, for example, property qualifications had cut the voting rolls back to one citizen in 200 – and France was actually one of the few continental kingdoms that even made that much effort to let people run their own country. Almost no one else even had constitutions. In Austria, censorship was so strict that it was generally assumed that whatever you wrote was illegal until the government said otherwise. Most writers circulated handwritten manuscripts for years among friends, getting advice on what to cut before they even attempted to pass it by a censor for printing.

All across Europe, even slow peaceful change was squashed, but the pressure continued to build. Liberals wanted to negotiate constitutions that put policy decisions and cabinet appointments into the hands of parliaments elected directly and fairly – not by everyone – just by solid citizens and householders. They wanted the right to gather, talk and write without interference.

Sometimes

social unrest seems to go in a generational cycle.

With each uprising, the participants either succeed and

grow complacent or fail and lose heart.

After the upheaval burns itself out, society needs to

wait for a new generation to grow up and get angry again before

momentum can resume. With Europe exhausted by the end of the

Napoleonic Wars in 1815, it took another 15 years for anything

interesting to happen again in European history. Then 1830

turned into a very busy year. The July Revolution in

France saw crowds in the street that chased out the

uncompromising King Charles X in favor of a new so-called

Citizen King, Louis Philippe, who acted more like the CEO of a

family business than God’s chosen embodiment of the nation.

Sometimes

social unrest seems to go in a generational cycle.

With each uprising, the participants either succeed and

grow complacent or fail and lose heart.

After the upheaval burns itself out, society needs to

wait for a new generation to grow up and get angry again before

momentum can resume. With Europe exhausted by the end of the

Napoleonic Wars in 1815, it took another 15 years for anything

interesting to happen again in European history. Then 1830

turned into a very busy year. The July Revolution in

France saw crowds in the street that chased out the

uncompromising King Charles X in favor of a new so-called

Citizen King, Louis Philippe, who acted more like the CEO of a

family business than God’s chosen embodiment of the nation.

Then Belgium gave it a shot. This Catholic, rapidly industrializing and coal-fired southern region of the Netherlands broke away from the Protestant, mercantile, wind-powered nation of Holland to set itself up as a new constitutional monarchy in the British model.

Then Poland tried to reclaim the freedom it had lost when powerful neighbors had divvied the old country among themselves, but the November Uprising in Poland failed to throw off Russian rule, and it became clear that the fire of 1830 had finally burned out. It would take another generation to crank up the protests again in 1848.

However, the 1830 uprisings sparked a smoldering fire under the British Monarchy.

Let’s back up a bit. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 had established Parliament as the last word in English government. After this, the English ruling class had things exactly where they wanted and coasted along without much change for almost a century. Of course voting was limited to the right kind of people – the ones with property. In 1780, fewer than 3% of the men in England and Wales had the vote. The Scottish electorate in 1831 was only 4,500 men out of a total of 2.4 million. Voting districts were traditional, predictable and unchanging, but as history moved forward, voting fell out of sync with reality. Places that had been given a seat in the House of Commons when they were thriving little market towns in the Middle Ages still had their vote now that they were abandoned ruins. Among the most notorious of these so-called "rotten" or "pocket" boroughs was Old Sarum, where eleven remaining voters in 1715, all minions of the local landlord, got to hand-pick two members to send to the House of Commons. Dunwich in Suffolk also got two members to represent its 32 voters in 1831. Meanwhile large, rapidly industrializing cities like Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and Sheffield had no voice in parliament. Parliament was far from democratic, but the government was fine with that.

![[British flag]](images/1801-Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.png) For several

generations British politics sank into comfortable slumber like

a well-fed gentleman in a padded chair sipping brandy before a

fireplace. Then the

American War of Independence shook British politics rudely

awake. The loss of the American colonies brought down Lord North

after 12 years as prime minister. Britain went through a year of

unstable coalition cabinets until the government finally landed

in the lap of the conservative Whig William Pitt the Younger in

December 1783. Pitt ran Britain until March 1801 and again from

1804 to 1806, which was long enough to become the center of a

stable clique of friends, followers and protégés. This Pittite

faction of the Whigs continued to run Britain most of the next

few decades until finally in 1834 Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel

officially organized the heirs of Pitt’s legacy into the

Conservative political party (nicknamed Tories).Ⓐ

For several

generations British politics sank into comfortable slumber like

a well-fed gentleman in a padded chair sipping brandy before a

fireplace. Then the

American War of Independence shook British politics rudely

awake. The loss of the American colonies brought down Lord North

after 12 years as prime minister. Britain went through a year of

unstable coalition cabinets until the government finally landed

in the lap of the conservative Whig William Pitt the Younger in

December 1783. Pitt ran Britain until March 1801 and again from

1804 to 1806, which was long enough to become the center of a

stable clique of friends, followers and protégés. This Pittite

faction of the Whigs continued to run Britain most of the next

few decades until finally in 1834 Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel

officially organized the heirs of Pitt’s legacy into the

Conservative political party (nicknamed Tories).Ⓐ

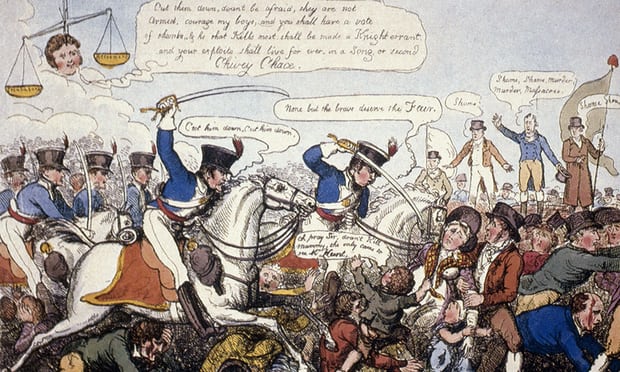

![Radical Henry 'Orator' Hunt, begins his speech to the crowd gathered at St Peter's Fields Manchester [Orator]](images/1819-before-Peterloo.jpg) The

reason an organized party had become necessary in the 1830s is

that the constitution (with a small-c) of the British government

suddenly changed, which threatened the underpinnings of

conservative (again with a small-c) rule in Britain.

The

reason an organized party had become necessary in the 1830s is

that the constitution (with a small-c) of the British government

suddenly changed, which threatened the underpinnings of

conservative (again with a small-c) rule in Britain.

Unrest had started to escalate in Britain

shortly after the Napoleonic Wars. Not everyone in England was

satisfied with the exclusion of the lower classes from

governing. The lower classes obviously weren’t, and they were

becoming less shy about making their displeasure known. On

August 16, 1819 a crowd of 60,000 to 80,000 workers peacefully

gathered at St Peter's Field in Manchester to request universal

suffrage and parliamentary representation. Local magistrates

watching nervously from buildings overlooking the square ordered troops to arrest

the speakers. Overeager cavalry unsheathed their swords and

charged into crowd, killing a dozen protesters and wounding many

hundreds more. This hacking and trampling of unarmed townsfolk

at St. Peter’s was sarcastically labeled Peterloo in

contrast to the glorious victory recently won at Waterloo.

from buildings overlooking the square ordered troops to arrest

the speakers. Overeager cavalry unsheathed their swords and

charged into crowd, killing a dozen protesters and wounding many

hundreds more. This hacking and trampling of unarmed townsfolk

at St. Peter’s was sarcastically labeled Peterloo in

contrast to the glorious victory recently won at Waterloo.

The Peterloo Massacre successfully squashed talk of reform for over a decade, but when the July 1830 revolution in France drove out their absolute monarch in favor of their Citizen King, the British ruling class panicked that maybe worldwide revolution was coming over the horizon again. Hoping to head it off before it got too far, moderates in the House of Commons introduced a bill to fix the most egregious problems with the electoral process; however, the Duke of Wellington - prime minster, victor of Waterloo and determined autocrat who had famously called his own soldiers “the scum of the Earth who have enlisted for drink” - absolutely and unconditionally refused to even consider lowering voting standards, no matter what the rest of Parliament said. He stubbornly kept reform off the agenda, which stunned even his Tory supporters. They nervously backed away from Wellington and started voting with the Whigs to bring reform forward anyway. Outmaneuvered, Wellington quit.

New

parliamentary elections saw reformist candidates elected in just

about every competitive constituency, with only the rotten

boroughs standing their ground on Wellington’s side. Under the

new prime minister, long-time reformer and tea namesake Earl

Gray, the liberal Whig majority in the House of Commons easily

passed a reform bill, but the House of Lords quickly vetoed it.

This sparked angry riots up and down England, especially in

Bristol where a few dozen protesters were shot down. Worried

this might get out of hand, King William IV agreed to create

enough new Whig peers to overwhelm the Tory majority in the

House of Lords. Rather than let this plan go through, however,

the Tory majority in the House of Lords gave up, gritted their

teeth and abstained from voting the next time the bill came

their way. This allowed the Whig minority in the House of Lords

to pass the bill in 1832.

New

parliamentary elections saw reformist candidates elected in just

about every competitive constituency, with only the rotten

boroughs standing their ground on Wellington’s side. Under the

new prime minister, long-time reformer and tea namesake Earl

Gray, the liberal Whig majority in the House of Commons easily

passed a reform bill, but the House of Lords quickly vetoed it.

This sparked angry riots up and down England, especially in

Bristol where a few dozen protesters were shot down. Worried

this might get out of hand, King William IV agreed to create

enough new Whig peers to overwhelm the Tory majority in the

House of Lords. Rather than let this plan go through, however,

the Tory majority in the House of Lords gave up, gritted their

teeth and abstained from voting the next time the bill came

their way. This allowed the Whig minority in the House of Lords

to pass the bill in 1832.

The 1832 Reform Act extended the vote to any man with a household worth of £10, which was a solid middle-class threshold. This increased the number of voters by 50%; it added 217,000 voters to an electorate of 435,000, giving the right to vote to about one out of five men or 5% of the total population. The least populous constituencies, including the most notorious rotten boroughs, were abolished and their votes were transferred to the largest of the unrepresented localities. It was far from one-man-one-vote, but it brought the geographic balance closer to reality. By bringing the middle class into government, it deflated a lot of reform talk without giving the vote to all those scruffy working class radicals banging at the door. Basically, it shored up the status quo for another generation.

-Matthew White

![[Previous Chapter]](images/previous_arrow.gif) |

![[Next Chapter]](images/next_arrow.gif) |

Ⓐ Alok Yadav, “Whig and Tory”, Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature (3 Dec. 2011) http://mason.gmu.edu/~ayadav/historical outline/whig and tory.htm

Copyright © June 2018 by Matthew White